"To most people, the Highlander is a long horned, shaggy coated, ferocious wild animal that can be dug out of a glacier after several years immersion, to continue its mastication of heather, bracken, stones, fence posts and preferably people, utterly immune to all forces of nature, including earthquakes and volcanic eruptions."

"To most people, the Highlander is a long horned, shaggy coated, ferocious wild animal that can be dug out of a glacier after several years immersion, to continue its mastication of heather, bracken, stones, fence posts and preferably people, utterly immune to all forces of nature, including earthquakes and volcanic eruptions."

(Donalda Badone 1928-2016)

Wildly exaggerated, of course, but the first time I laid eyes on a Highland cow, those words from the British Highland Breeders' Journal seemed quite apt. My husband and I were travelling on the Island of Mull in the Scottish Hebrides, and we had pulled off the road onto the unfenced moor for lunch. A group of these shaggy, long-horned beasts suddenly loomed out of the mist. Although somewhat taken aback, we couldn't help but be fascinated by their rugged, romantic appearance.

Now, several years later I know that the writer did have a point. Although anything but "ferocious", a Vancouver Island breeder of our acquaintance has a hard time fending off her "pets" as they vie for the sensuous pleasure of being scratched with her curry-comb. The Highland's greatest asset is its hardiness, its vigour in cold temperatures and its ability to thrive on the roughest of range. While I can't say that l've seen a Highland beast dug out of a glacier, it probably wouldn't look very different from ours on a January morning.

That first impression in Scotland led to our having a growing interest in the prehistoric-looking creatures, and eventually to our own involvement in raising Highlands back home in Ontario. This was partly a "roots" thing, since my father had come from Scotland, but perhaps too, we were still a little under the spell of the Hebridean Islands with their magical landscape and their insular Gaelic culture surviving in the lonely crofts and harbours. As it happened, somebody knew somebody who had Highland cattle. The result was that two years ago, six cows with calves at side spent four days and nights travelling from Alberta to Ontario in a cattle truck. When the ramp was finally lowered to our field in Willowdale, the long-travelled animals scarcely uttered a moo before settling down to serious grazing.

Originally bred in the Highlands and the western islands of Scotland, an area well-known for severe winters, rugged terrain and winds that sweep in from the Atlantic Ocean, the Highland breed seems custom made for our climate. Although unpopular with most commercial beef breeders because of their relatively small size and their only middling performance on good grasslands and in the feed lot, Highlands are in their element on poor land. There are registered herds in every province west of Quebec, as well as in Alaska and the Northwest and Yukon Territories. We recently visited the farm of Henry Carse, a breeder in the mountains of Vermont, who feels that Highlands may be the answer to a commercially viable beef industry on the restricted diet provided in those inhospitable hills.

As one might suspect, no significant change has occurred in the physical conformation of the Highlands for centuries. In fact, they closely resemble the Boslongifrons or Celtic Shorthorn, one of the earliest known domestic races of cattle. While most cattle are believed descended from the Aurochs (primitive ox of Central Europe), the Highland traces its remote ancestry to the Celtic ox, which was smaller than the Aurochs and had the dished face that is characteristic of the Highland.

Domestic cattle had to be almost as hardy as the ancient ox to survive a Highland winter. Those needed for meat were butchered in the fall, but the rest were wintered over with so little feed that by spring they could scarcely stand in their "byres" - stalls that were often divided by only a partition from the family living quarters in the tiny, thatched stone cottages. Each crofter cultivated his own small plot of land and raised his Highland cattle for milk, meat and hides, and to pull his plough and wagon.

Queenly Choice

Agricultural practices improved, however, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, and cattle owners became interested in selectively breeding their livestock to upgrade the most valued characteristics. The Highland became known as a beef breed, rather than primarily as a milker.

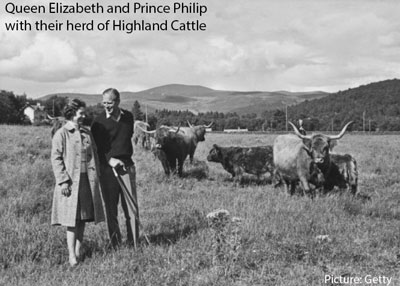

The Highland Cattle Society of Scotland was established in 1884. Its present patron is Queen Elizabeth, who has a herd on her Balmoral estate. Highlands are now established all over the world, especially in colder climates, and breeders' societies have been formed in the United States, Sweden and Canada where the Canadian Highland Cattle Society was founded in 1964.

The Highland Cattle Society of Scotland was established in 1884. Its present patron is Queen Elizabeth, who has a herd on her Balmoral estate. Highlands are now established all over the world, especially in colder climates, and breeders' societies have been formed in the United States, Sweden and Canada where the Canadian Highland Cattle Society was founded in 1964.

Each spring and autumn the most important Highland show and sale is held at Oban, Scotland, drawing buyers from Denmark and Sweden to vie with New Zealanders and Americans in paying top prices for the champions. The prize male in the most recent sale was Jock 20th of Leys, who sold for 1500 guineas, almost $4,000. The impetus behind most of this competition can be understood by a recent article on Highland cattle in Sweden that appeared in the Highland Breeders' Journal. "The scope for a breed which can exist outside with minimal attention, having good mothering quality, good foraging ability, and which can provide well-fleshed, fat-free carcass is tremendous, and these are all qualities that the Highland breed has in abundance."

Those who presently have herds are enthusiastic and convinced after one of the worst winters experienced in Scandinavia for a long time. Calves were born and nursed in considerable depths of snow in extreme temperatures and survived. The herds were generally fed on pole dried hay and given a little shelter where they could feed .... usually open fronted sheds ... but with many herds this was not available.

Here in Canada, animal scientist John Lawson has done considerable research since 1956 with Highland cattle at the Agriculture Canada research farm at Manyberries, Alberta. "Highlands " he says, "are being used in areas of Canada where other breeds won't reproduce and in some cases won't even survive."

Lawson has studied the productivity of Highland and Hereford dams over a five year period at the Alberta station, and his resulting figures are based on herds of 100 cows kept under "short-grass prairie range" conditions. The purebred Highland cattle produced almost a ton more calves than did Herefords under the same conditions. Highland- Hereford cross dams were the best performers of all three.

(See the results of John Lawson's research in the "Manyberries Experiment" in our Feature Articles.)

The Highland's vigour was proved by a University of Alberta study comparing bison, yak and two breeds of domestic cattle, Hereford and Highland, for their ability to survive and reproduce in a northern environment. The traits examined included "ability to utilize forages of varying quality, metabolic response to cold, and behaviour". The lowest critical temperature was discovered, below which the animal has to divert energy away from growth and production in order to maintain body heat.

As could be expected, the bison were hardier than the domestic cattle, but the Highlands equalled the yaks and exceeded, in ability to withstand cold, the Hereford, the common "red white-face", the world's most popular breed of beef cattle.

Lazy Man's Jersey

Our Highlands stayed outside through all the snowy months without noticeable discomfort, only moving to the lee of the barn or the shelter of the woods when the cold wind blew from the north. Calving on the snow was accomplished without any trouble.

David and Nancy Pease of Ontario discovered the characteristic vigour of Highland cattle quite by accident. Like us, they were first introduced to the animals touring a trip to Scotland, and bought two cows "as pets" when they returned home. "Their Herefords, on the other hand," says Nancy "were serious cattle." But the next spring the Highland raised more calves than the Herefords and David said, "Maybe there's a lesson to be learned here " So the Peases returned to Scotland and bought the grand champion Highland bull from the 1973 spring sale at Oban, Leodhas of Douneside, as well as seven cows and two bull calves. Two years later they imported six more females from England In the meantime, they were discovering that, crossed with heavier beef bulls - Simmental, Welsh Black "Hereford or Tarentaise - the Highland or Highland-X-Hereford cows would throw big calves and would produce enough milk to raise them well. To their advantage, the cows were themselves small animals, and so were economical to winter.

In addition, the Peases crossed a straightbred Jersey cow with "Leodhas", to produce what Nancy describes as "the lazy man's Jersey", a cow that produces creamy milk in slightly less quantity than a jersey but, from a health view-point, is more resilient than a Jersey and does not suffer from milk fever an ailment common among heavy milk producers. "She has no problem with calving, either, and has been bred every year to a Hereford bull," says Nancy. "She's a small cow, about 900 pounds, Highland red, smooth-furred in summer with hair about three inches long in winter."

Good milk production is just one reason that Highlands are considered among the best of mothers. They also have a higher conception rate than most breeds. While a cross country estimate of the ratio of "calves weaned to cows bred" is about 70%, Lawson's figures from the Alberta research station indicate that the rate for both Highlands (79) and Highland crosses (82) exceeds the average. Added to this is a strong maternal instinct in the Highland strain. Abandoned calves are unknown, even for first-calf heifers. A cow is almost constantly by the side of her young, unlike other breeds which often allow their calves to forage at some distance. In a letter to the Scottish publication, "The Field", a Hope Springs, British Columbia rancher wrote, "Highland cows are the best mothers I know in wolf and bear country. Their calves are always with them." Too, because of their small-headed, short necked conformation, they seldom have difficulty in calving." Highland crosses share this advantage, as the breed is somewhat smaller than the beef cattle to which they are usually bred — Highland bulls weigh between 1,500 and 2,000 pounds, and a Charolais, about 3,000 pounds. The result is problem-free, unassisted births with a high survival rate.

Another advantage of the breed is its ability to convert practically any forage into meat, and first generation crosses seem to retain this ability. Scottish breeder Captain D.S. Bowser writes, "The cross Highlander has the inherent hardiness of the pure Highlander, plus hybrid vigour, together with the Highlander's foraging proclivity. Once they have cleaned up their daily feed, they scatter across the hill, picking up what they can, rather than standing about bawling for the next feed, and there is no doubt that they are able to make use of poor quality grazing and roughage." In short, Highland cattle will eat fodder that another breed would not touch.

Lean Qualities

This does not mean, however, that a conscientious Highland owner will abandon his animals to the elements every Fall, as the poor Scottish crofters once did. These animals appreciate the same care and feeding given any other breed, although they can be expected to use that care to greater advantage when the weather and pasture are poor.

The acreage required per head per year ranges all the way from one to 60 depending upon the quality of the pasture, the age and condition of the cattle, and whether a supplement is fed. About 20 pounds of grass-legume hay is recommended as daily ration for wintering yearlings which will be pasture-finished the following summer. If the hay is comprised solely of grass, a protein supplement like corn will be needed. Our animals wintered well on half a bale of mixed hay a day each plus a thrice-weekly oat supplement. Although they contentedly browsed our cedar brush between feedings, the thunder of the roller grinding their oats precipitated a general stampede to the feeding trough and much lowing if they weren't fed fast enough. In a 1975 report by John Lawson entitled "Feedlot and Carcass Traits of Steers of the Highland and Hereford Breeds and their Reciprocal Crosses based on the Manyberries Project", Highlands were found to be about as efficient in converting feed into meat as were the other animals studied. But, primarily because of its small size, Lawson recorded, "The Highland was inferior to the other groups for most of the traits studied (final feedlot weight, average daily gain in the feedlot, cold carcass weight and dressing percentage). It has a slower growth rate and poorer fattening tendencies in the feedlot and cannot be recommended as a pure breed in this environment. The reciprocal cross calves, on the other hand were essentially equal to the Hereford in all respects, except for a trend to a lower percentage of choice and good grades."

The grades "good" and "choice" signified, among other things, a certain fat content in the meat, and it was the Highland's unusually lean beef that often disqualified it from these classifications. The ability of a carcass to take top designation, and therefore best price, is of great importance to the commercial beef producer, but Lawson states that the additional fat cover "does not necessarily bear a relationship to carcass quality". Highland beef is lean, a quality that is actually becoming increasingly popular.

Neil Hulbert, a California rancher who owns a meat processing plant, was having a problem with too much fat and waste. "Then," he says, "I bought a Highland bull, Wildemere Lochinvar." He bred him to Shorthorn cows and crossbred heifers and soon was producing leaner beef. "The doctors say the outside fat is what causes heart trouble." says Hulbert. "The Highland beef has a very fine marbled texture in the muscle, and very little fat outside." Lawson points out that the leaner meat is a function of a slower growth rate. Both straight bred and crossbred steers in his study dressed out at close to the American average of 60 percent of live weight, the purebred Highlands slightly below, the crossbreds slightly above. The percentages of the more valuable cuts were the same. One slight difference was that both Highland and Highland-Hereford steers produced more chuck and less plate-shank beef than the others.

Valuable Coats

We were sold on Highland beef when we attended the annual meeting of the Society at the Pease farm and sampled the piece de resistance, a joint of mouth-watering Highland beef. Tender, delicious and marbled with fat, it is a gourmet treat at exclusive restaurants like "Simpsons-in-The-Strand" in London, England. Perhaps Britons still feel, as Daniel Defoe said they did in 1727, when large herds of Highland cattle were annually driven down to markets in southern England. "The beef is so delicious for taste," wrote Defoe, "that the inhabitants prefer 'em to the English cattle."

But delicious beef is only one product of the butchered Highland. Beautiful couch throws and rugs have been made from the luxurious hides of these long-haired beasts. Highlands owe their winter hardiness in part to this coat. The hair is long and naturally waved. It is produced in a double layer, a downy undercoat and a long outercoat, which is well oiled to shed rain and snow, and it may reach more than a foot in length. Much of the long hair is lost in the summer, so Highlands are most photogenic during the winter months. The hair itself, combed or collected from fences and posts where it is rubbed off in spring, is in demand for weaving. And the long, sweeping horns - usually upturned in the females, down in the bulls - are valued for the wall decorations or in the production of horn merchandise. In Scotland, a thriving cottage industry turns out horn spoons, knife handles and other small implements.

But delicious beef is only one product of the butchered Highland. Beautiful couch throws and rugs have been made from the luxurious hides of these long-haired beasts. Highlands owe their winter hardiness in part to this coat. The hair is long and naturally waved. It is produced in a double layer, a downy undercoat and a long outercoat, which is well oiled to shed rain and snow, and it may reach more than a foot in length. Much of the long hair is lost in the summer, so Highlands are most photogenic during the winter months. The hair itself, combed or collected from fences and posts where it is rubbed off in spring, is in demand for weaving. And the long, sweeping horns - usually upturned in the females, down in the bulls - are valued for the wall decorations or in the production of horn merchandise. In Scotland, a thriving cottage industry turns out horn spoons, knife handles and other small implements.

Anyone living in the country with a small acreage can experience the many satisfactions of owning Highland cattle. One way, of course, is to buy a cow borrow a bull or use AI (artificial insemination) from a registered sire and produce the beginning of a cross-bred herd or at least next years beef. The Society is the best source of information on the breeders and local herds. Prices of cattle fluctuate, naturally, but are comparable with those of other cattle, even though the Highland is rarer than many other beef breeds in North America. There are just 55 members in the Canadian Society most of them in British Columbia and Ontario.

Perhaps the easiest way to raise a Highland is to put a steer on grass for the summer and butcher it in the Fall. Even better is to have a succession of steers coming to maturity at two or even three years of age. This way, the first year's steers would be kept over until the Fall of the second year, another yearling being purchased each spring.

The result will be a freezer full of remarkable lean beef. But there is another benefit, one interestingly, of questionable merit. Aesthetically, Highlands are the most pleasing of cattle. Despite familiarity, each time we catch sight of one of these magnificent animals against the green of the fields, the dark of the bush or the white of the snow, we get a shock of pleasure. The sight of a herd of mixed colours, red, brindle, black, yellow, white and dun is simply breath-taking.

In fact, the Highland's beauty and its ability to conjure compelling memories, or imaginings of the wild Scottish countryside sometimes urges the business instinct out of Cattle owners. "People will keep a beast that would have been culled if it had been any other breed," says Nancy Pease. "There are a great many scruffy ones here (in North America), zoo types. A great many of our sales go to hobbyists, but we hope they will raise thern as cattle, too. Some people keep Highlands for strictly sentimental reasons. I feel sentimental about them, too, but we select very carefully for commercial qualities, calving every year safely, and producing good calves."

The sentimental Highland owner can well be understood. Not only is the animal beautiful, even a scruffy one, but its owner taps into a wellspring of colourful tradition. Seemingly unpronounceable Gaelic words are woven through the lore of Highland raising.

The Journal of the Canadian Highland Cattle Society is called "The Kyloe Cry". Highlands are often called "kyloes", a name which is believed to be derived from the Gaelic word for strait. On their journey to southern markets, the cattle would often have to swim across these straits or "kyloes".

All pedigree calves born in one year are assigned the same letter designation, and are often named accordingly. When it comes to naming Highlands, it's a help to know a little Gaelic. In 1979 the letter was 'L' - Loachag (Little Heroine) might have done for a Heifer, or Lasgaire (Champion) for a bull calf.

There is no 'K' in Gaelic, but 1978 was the 'K' year. We very much wanted authentic names for our six calves but had to compromise a little. They have a Gaelic sound but not a Gaelic spelling. Our farm name is Cnoc Eilidh (Ellen Hill, pronounced Knock Elly) so we have four heifers called Knockbain (Fairhill), Knocklea (Grey Hill), Knock- angle (Hill of the Barn), plus two bulls called Knockantarbh and Knocknacean, (Hill of the Bull and Hill of the Heads).

Gaelic terms are usually used to described colours: Ruadh (roo-ak) is red; buidhe (boo-ey) is yellow; geal is white; riabhach (ree-vak) is brindle and dubh (doo) is black. Fond owners might call a bull Prionnsa Dubh (Black Prince) or Gille Buidhe (Golden Boy). Of course, shirking romance, more than one breeder has reverted to the old familiar bovine names like Buttercup, Duchess and Bossie. One of the most charming bits of Gaelic tradition surrounding the tending of Highland cattle is a benediction, which was sung in former times as the kilted Scottish cattleman sang to his herd as he drove them to pasture in the morning.

Closed to you be every pit,

Smooth to you be every hill,

Snug to you be every bare spot,

Beside the cold mountains

The sanctuary of Mary Mother be yours,

The sanctuary of Brigit the loved be yours,

The sanctuary of Michael victorious be yours,

Active and full be your gathered home,

The protection of shapely Cormac be yours,

The protection of Brendan of the ships be yours,

The protection of Maol Duinne the saint be yours,

In marshy ground and Brocky ground,

The fellowship of Mary Mother be yours,

The fellowship of Brigit of Kine be yours,

The fellowship of Michael victorious be yours,

In nibbling, in chewing, in munching.

About the Author

DONALDA EWART BADONE (Née Hastie)

1928 - 2016

Donalda (Donnie) was born in Toronto on April 17, 1928.

Her youth was marked by the Great Depression, her father's death at age six, and World War II. As a teenager, Donnie worked at the Yorkville Branch of the Toronto Public Library. She graduated from Oakwood Collegiate in 1945 and attended Victoria College, working at working at the Canadian Bank of Commerce in Toronto after completing her BA.

Through a friend from Oakwood and Victoria, Jackie Austin (now Myers), Donnie met Louis Badone, her future husband, and they were married in 1953. After living in Haley Station, near Renfrew, Ontario for three years, they returned to Toronto, started a family and lived for nearly 50 years in Willowdale. After the tragic death of their second daughter Victoria in 1966 from cerebral palsy, Donnie decided to return to the University of Toronto and obtained a degree in library science as well as teacher's qualifications. She worked for many years as a school librarian at Drewry Avenue Public School in North York, helped organize Scholastic Book Fairs, and wrote numerous reviews of children's books for library journals.

In the 1970s, she started a second career as a freelance journalist and published articles on topics including Highland Cattle (Harrowsmith Magazine), Paisley shawls, Peruvian textiles and antique hooked rugs. Later, she published three books. The first, The Complete House Detective (Boston Mills Press, 1988), chronicled the history of her Willowdale home, built in 1834 by pioneer Elihu Pease. She also published Dundurn Castle (1990, Boston Mills Press) and The Time Detectives (1992, Annick Press), an introduction to Canadian archaeology for young people.

In 1972, Louis and Donnie decided to purchase and restore a log house near Lakefield, Ontario and started another career as part-time farmers, raising Highland Cattle for over a decade.

The Harrowsmith Magazine article (this one) was first published in January 1980 and as a result the membership of the Canadian Highland Cattle Society almost doubled, jumping from 81 members the previous year to a record breaking 156 members.

They also travelled extensively in Peru, Senegal and China, where Louis volunteered for Canadian Executive Services Overseas and Donnie continued her writing career, contributing letters to CBC radio's Morningside.

Donnie was an active volunteer in many organizations: the North York Historical Society, the Ontario Heritage Trust, the Ontario Archaeology Society, the William Morris Society of Canada and the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society.

In 2003, after ensuring the preservation of their historic house in Willowdale, Louis and Donnie moved to downtown Toronto.

Following Louis' death in 2012, Donnie lived at Hazelton Place Retirement Residence. Donnie passed away peacefully at Joseph Brant Hospital in Burlington, Ontario on July 26, 2016, in her 89th year.